Welcome to another episode of good and bad choices I’ve made in my home landscape. Previous posts in this series cover hardscape; beds, berms, and swales; living mulch; and fencing. Today’s post again feels very personal, and I want to give a disclaimer that while some of the things I’m discussing today may or may not work for others, I’m sharing how they worked for me.

We live on the dry boundary of the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains. We receive about 20 inches (51 cm) of precipitation per year, peaking right around now. The problem with gardening in this relatively arid environment is that many Colorado residents moved here from somewhere else, usually somewhere wetter and greener. Because culture and sentiment drive landscape choices, they often want to replicate that here, whether it’s appropriate in terms of our resources or not. (I grew up in western Colorado, with half the precipitation of Boulder, so my view is that this place is absolutely lush.) As a result, a lot of Colorado urban landscapes do not reflect our water realities, and it can be hard to find landscape professionals who are in tune with nature and regenerative choices, though climate change and our increasingly severe droughts are changing that.

When we made a lot of our landscaping choices twenty years ago, we were smart enough to know that lawns are for playing on, and we kept our lawn to the backyard only, where the kids were. Irrigated turf can be a legitimately good choice when it serves a purpose: space for kids and pets to play on and defensible space near structures in high fire risk areas are great reasons to have it. We knew that lawn irrigation systems are cranky and prone to failure, wasting water and needing regular maintenance. We chose to go with a subsurface irrigation system, which can use a fraction of the water surface emitters do, which was well intentioned.

HOWEVER. I did not assert myself with the landscaper. He estimated our soil to be much more clayey than it is. I’m trained as a plant ecologist and soil scientist; I had done a textural analysis on our soil myself and pegged it as a sandy loam. (The Natural Resources Conservation Service soil survey agrees with me.) Sandy soils drain more quickly and don’t have as much capillary action (sideways movement of water through surface tension) as clayey soils when it comes to water infiltration. The end result is that the subsurface lines were spaced too widely, as if for a clayey soil, and too deep. When we had a wet year, the lawn looked fine. When we had our frequent dry years, the lawn was striped with green areas that were over the lines and brown areas between the lines. We complained, we went up the food chain, and it was to no avail. As our kids have grown up and are leaving the nest, we have chosen to let the lawn die and to replace it with more sustainable habitat and to rethink our landscape. I absolutely do not recommend Netafim lawn systems. Problems such as ours require a complete replacement.

We did some drip emitters to support low water plant choices outside of the lawn, but I would describe drip as not the best choice for me. When watering happens automatically, people just use more water. When watering happens by hand, less water gets used; people will not water when plants and weather indicate it’s not needed. (Research backs this up.) Drip emitters made me lazy and allowed plants to get watered whether they needed it or not. Drip emitters also need maintenance; leaks waste water. I hate checking and maintaining them. For me, a better choice is low water native plants that I water by hand to get established and then which need little to no water thereafter. (I water trees regularly because of climate, and I will water the landscape when it has been a long time since any precipitation.)

My best watering choice for getting plants watered with low effort and automatically has been to learn how to harvest precipitation and garden for the rain. Last summer and fall, my family and I surfaced four of our downspouts and redirected them to basins or lower areas protected by small berms. We calculated our roof area and the volume of precipitation in typical storms and how much these basins could hold. We then planted them with native plants and mulched them well. The mulch helps the infiltration of the water, and these areas will stay moist longer than the rest of the soil. We expect to have to do a little hand watering in the heat of summer this year if these new plants haven’t received precipitation in a while, but otherwise, little hand watering will happen. This is the best of all worlds: it requires observation and tweaking to maintain, but it’s less overall than drip or other irrigation. Water gets directed to plants which need it. We use much less water overall.

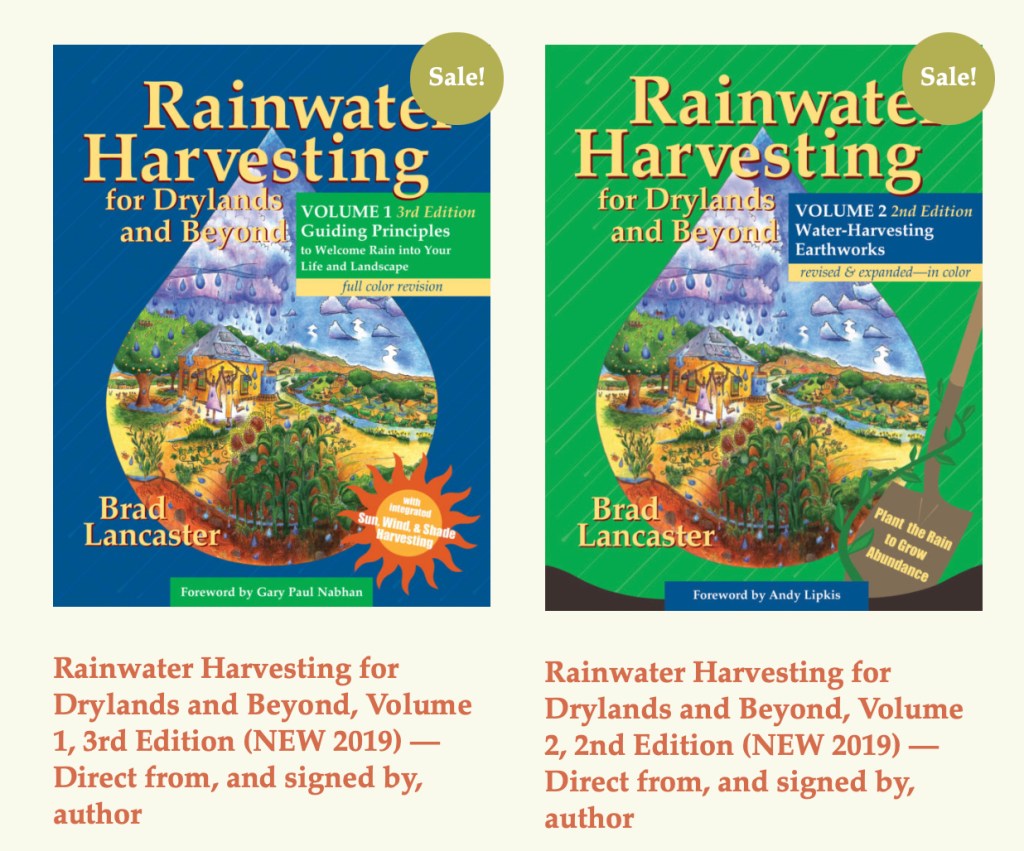

If you are curious about rain gardening, I have a few suggestions. The first is to read Brad Lancaster’s books (Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volumes 1 and 2). A local group has formed, and we are discussing precipitation harvesting (contact me if you’re interested: I’m coordinating it). Or just engage in a conversation with me about it. If you see me out in the rain look at my downpipes, come say hi and take a look.

Leave a comment