Sometimes, I feel I have to explain why there are “so many” sunflowers in my yard (when internally, my perception is that there is certainly more room for more sunflowers of all types). Talking with my son, a newly minted landscape architect, a native plant master, and an all-around good guy, I mused over the fact that while everyone seems to love sunflowers, no one seems to want them in their yards. Rather… they hold a platonic ideal of sunflowers, and don’t want them in their yards if they are “too”: too big, too messy, too far out of bloom, etc. He replied that sunflowers are in the uncanny valley of landscaping, and that seems like the perfect metaphor for further pondering.

People adore sunflowers. Which people? Pretty much all people. The Biota of North America Project maps 67 species of sunflowers native to the United States, with over 150 species total with a few more native to Mexico, Central America, and South America. They have been used for food (Helianthus tuberosa for their roots; many other species for their seeds), dye (petals), medicine (all parts), and structural strength (the stems are quite light and strong). Via the earliest North American colonizers, sunflowers made their way to Europe, where they were grown, hybridized, and beloved to the point that Ukraine is the largest grower of sunflowers for food in the world, and sunflowers have become a symbol of that country. Vincent Van Gogh’s acclaimed painting series on sunflowers captures and communicates the universal living beauty of sunflowers. Various species and hybrids are extremely popular garden plants and cut flowers worldwide; check out any seed offering at a garden shop or the display at a flower shop. Sunflowers populate children’s art from their earliest ages. When they emerge on roadsides, hellstrips, and in wildlands, people rejoice at seeing them.

Like no other flower in my region, wildlife love sunflowers. Stop and watch a sunflower plant of any type, peer into a sunflower in bloom, or step in to examine the buds, stems, and seed heads of a plant. Generally a cloud of insects floats around the entire plant (often small bees and other Hymenoptera, like wasps and sawflies, but also pollinating flies, predators like assassin bugs and ambush bugs, and beetles). Torn petals indicate that precious goldfinches may be browsing to amp up their feather color and signal their breeding fitness. Plants gone to seed bob, as small songbirds alight on seed heads to peck out seeds for dinner.

I trained as a Pollinator Advocate in the City of Boulder program, and I participate in Cornell Lab’s FeederWatch. I’m a native plant master and active in conservation groups. I continuously seek out additional learning opportunities about plants and wildlife, and I read voraciously, listen to podcasts, and attend talks and webinars. Sunflowers are a keystone plant for wildlife. Period. This genera supports countless native bees, butterflies and moths (per the research entomologist Doug Tallamy and horticulturist Jarrod Fowler, 89 species of bees specialize on these plants and 58 species of butterflies and moths use them as the host plant for their young). Sunflowers also support a huge number of birds, including individual species from the following families: wrens, woodpeckers, wood warblers, waxwings, vireos, thrushes, sparrows, blackbirds, nuthatches, mockingbirds, finches, corvids, chickadees, and buntings. (And all without the hygiene issue of bird feeders, which ironically are often stocked with… sunflower seeds.) For my region, there just isn’t another type of non-woody plant that provides as much wildlife support as sunflowers.

I have described compelling arguments for sunflowers as historically and and geographically popular plants for human beings and beyond. However. Multiple times this year, in my presence, people who ought to know better have denigrated sunflowers of various stripes as not appropriate for home gardens. Enter the uncanny valley.

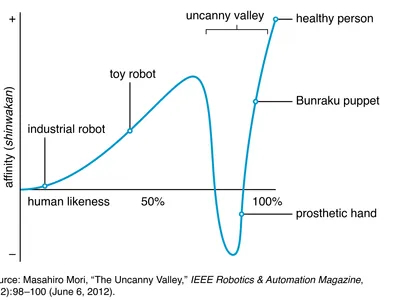

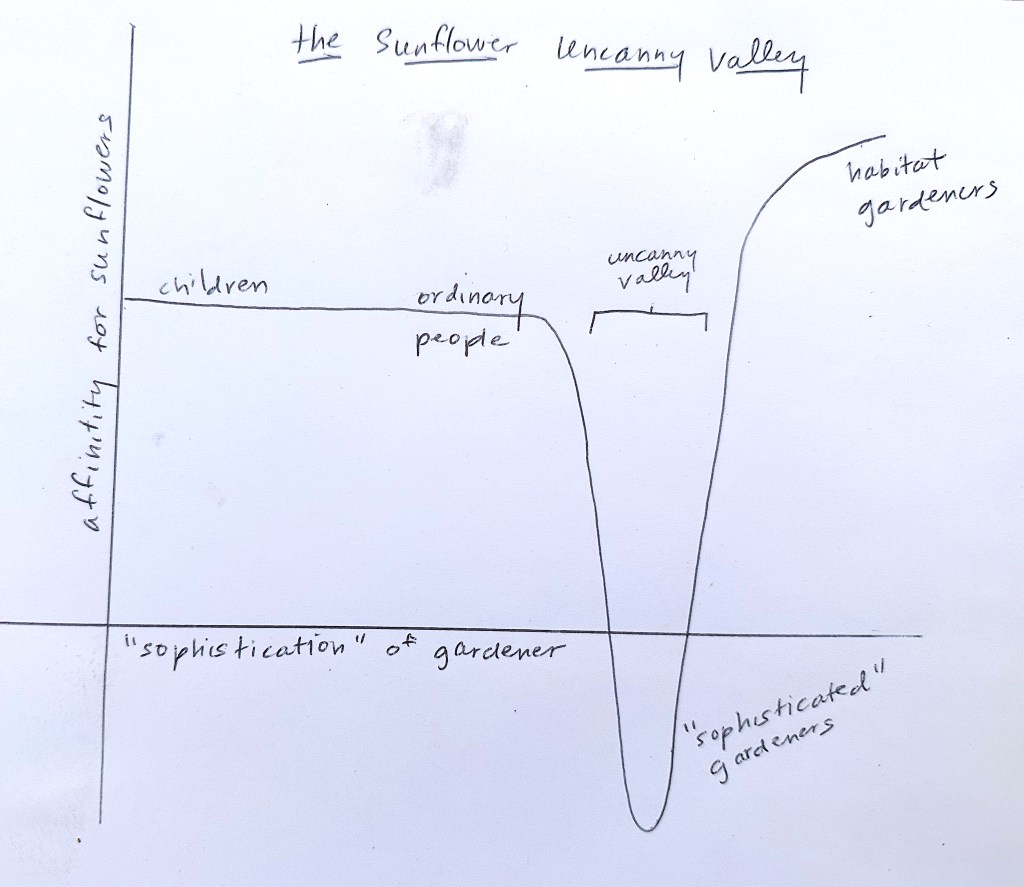

The uncanny valley comes from a field entirely unrelated to gardening—generally it describes how human beings respond to anthropomorphism in robotics or animation—but hear me out. A well known theoretical curve describes the uncanny valley: the x axis shows how humanlike an animation or robot is, and the y axis displays affinity: how much enjoyment or revulsion we feel in response. When human likeness is low, our affinity is low but positive, rising as human likeness grows. At a certain point of high likeness, affinity plunges into negativity (revulsion). At very high likeness, affinity skyrockets to its highest level; we have the highest affinity for robots and animation which are 100% lifelike. I propose the following for a sunflower uncanny valley: on the y axis again is affinity (for sunflowers), but on the x axis, we find “sophistication” of gardener (this is a bit tongue in cheek). People who are not gardeners, people who love flowers just for their sake, children, and generally all people everywhere delight in sunflowers. But as adults becoming more regimented (“sophisticated”) gardeners, they buy into a certain culture around gardening and are liable to fall into the sunflower uncanny valley. Things have to look and behave and be maintained a certain way lest they be considered messy or weedy or likely to attract vermin or the dread “liable to lower property values.” Messy: not boring and lifeless like the monoculture lawn which blankets suburbia. Weedy: not comprised of the exotic alien landscape horticultural specimens we have come to expect in urban and suburban yards. Likely to attract vermin: actual living creatures native to this area utilize this plant. Liable to lower property values: this is a classist, racist fantasy fed not by your community and your people but by forces urging you to conform and try to wring the last dollar out of your home, your nest, your refuge. In short, there exist people who consider themselves to be sophisticated gardeners who will tell you that you shouldn’t grow sunflowers in your garden. Try to rise above their message and become a fully actualized habitat gardener who recognizes both the beauty of the sunflower and its high value in a living landscape.

We are in the midst of unprecedented danger for our planet, all of its inhabitants, and our very future. We use too much fresh water on landscapes which don’t provide a whit of ecosystem services in return. Pesticides to prop up exotic plants struggling outside their nature range soak the earth and poison non-target species. We indiscriminately dump nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, extracted at great environmental cost, on landscapes, only to create hulking dead zones in our estuaries and oceans. The population of songbirds in just North America has dropped by 3 billion since 1970, and the biomass and number of insects has dropped by nearly half and nearly two thirds, respectively, in Colorado since the 1980s. Surely sunflowers, so thrifty in their need for water and nutrients, so generous with the ecosystem around them, surely we need this highly valuable group of native species in our yards?

My advice: start with planning, and see them as they are. My sunflowers (Helianthus anuus, H. tuberosa, and H maximiliani) are all big plants. Think of them as shrubs instead of forbs; this will help your garden vision and spacing. Considering placing these big sunflowers along chainlink fences, if you have any. They provide a visual screen to neighbors’ yards, and the fences provide a support. Do not overwater or overfeed: all of these plants need strong stems to stay upright. Too much water and too much nitrogen lead to floppiness. Consider support: wire structures which support tomatoes and peonies, put in place midsummer, help keep plants upright (we certainly don’t stop recommending or growing these other plants just because they do they same thing sunflowers often do). Resist the urge to cut them down after they have finished blooming; the prime time for bird feeding comes after the flowers finish blooming. Remember that birds can contract communicable diseases from bird feeders which are too crowded or which don’t get cleaned frequently enough, whereas sunflowers provide free, clean, season-long bird feeders. In the spring, cut stalks to 12-24” high, to provide habitat for stem-nesting bees (see Heather Holm). Last but not least, communicate and share, so that others know what you are up to and can appreciate it. I have signs in my yard indicating that I support pollinators and habitat. I share my thoughts about habitat gardening on my pollinator post and elsewhere. I share seeds and plants with others. I really want all us to get to that point of fully actualized habitat gardeners who get maximum joy from these amazing plants.

Leave a comment